Designers in Residence

Q&A -Mále Uribe Forés

To mark International Women's Day, the Design Museum caught up with one of this year's designer in residence, Mále Uribe Forés, the architect and designer behind Salt Imaginaries.

#DesignersinResidence

Q:Tell us a little bit about your background?

A: For the last 7 years I have been working in varied projects around exhibition design, spatial design and art installations. I moved to London from Chile in 2015 in search of opportunities to work in a more multidisciplinary way. Here I started working at Storey Studio as a spatial designer for exhibitions and fashion projects. This was a fantastic turn in my career as it allowed me to work with space from an artistic and more fluid approach. With the Creative Director Robert Storey and an amazing group of creatives, I had the chance to work with incredible brands like Hermès, Nike, or museums like the V&A, designing sculptures, window displays, exhibitions and retail spaces. I then got a scholarship to complete my Master degree at the RCA in Information Experience Design, where I had the chance to explore further my personal art projects in surface design, lighting and material culture in architecture. I still work at Storey Studio focusing on art-initiated projects, while also teaching at the RCA and developing my personal practice in art and design..

Q: What is ‘Salt Imaginaries’ all about? What inspired you to work on such a project?

A: Salt Imaginaries is a project that investigates new possibilities for disregarded materials, focusing on salt from the Atacama Desert in Chile.

I am interested in questioning the way we perceive and give value to materials as cultural constructs. After visiting the desert a few times, I became fascinated with the geological richness of the territory and the complex overlaying narratives that coexisted there. I was particularly interested in salt… it is everywhere in the desert and its different states and formations are fascinating. It is also a material that is in the middle of different mining and extraction processes and conflicts. As such a transformative material, it stuck in my mind and I decided I wanted to tell stories about this unique territory through the lens of salt.

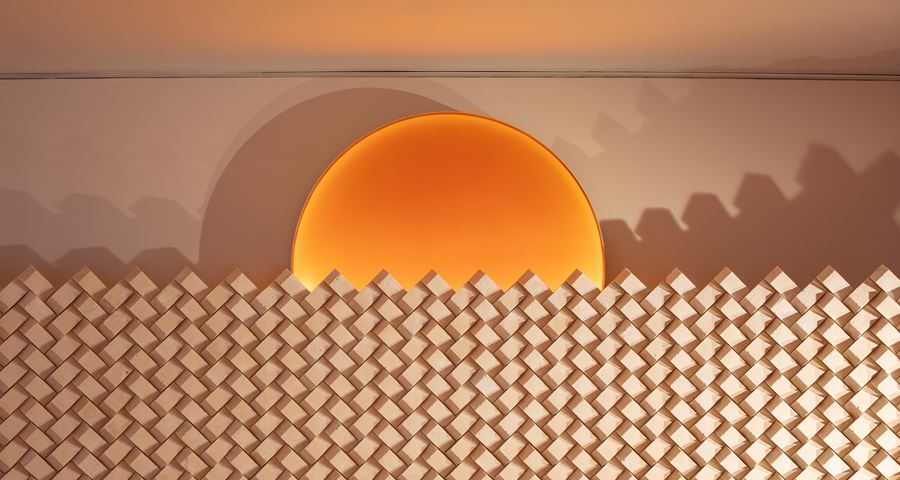

On a practical level, I wanted to keep working with surface design. I have always been fascinated by the immersive qualities of geometry, materials and light, but this time I wanted to focus on the narratives behind it. I ended up creating a wall made of around 1300 tiles of salt and plaster that are continually interacting with the environment. On a short timescale, a dynamic light system activates the wall to turn it into a performative and kinetic surface. On a longer timescale, the wall is physically changing: salt is reacting to the humidity and temperature of the room, exponentially crystallising and evolving over time as a living system. In the context of the boom of bio-materials and the environmental crisis, making visible the transformative power of materials is key for me as a designer. Ultimately, the wall is the result of an experimental process with different disregarded salts from extraction processes in the Atacama. Giving value to a discarded salt through design, I intended to turn it into something new and unexpected to the public.

Q: How does your project respond to this year’s Designer in Residence theme, “cosmic”?

A: Minerals can take us back to the origin of the cosmos. They are inorganic natural formations, raw materials, heavy rocks, precious metals and creators of the universe. Studying minerals can be, in a way, studying the formation of the human species in history: from the mysteries of the Big Bang and other interplanetary connections, to the current environmental and humanitarian challenges we are facing in forgotten territories like the Atacama. Here, minerals have shaped territories and civilisations, ecosystems of rich microbial life, ancestral cultural cosmologies from the Andes, and moreover, an ongoing history of resource extraction and international geopolitical conflicts.

This extreme landscape is intrinsically connected with studies of the cosmos: it’s extreme aridity, clear skies and saline qualities turn it into a landscape that gathers astronomers, geologists, archaeologists and scientists from all around the world to study the origins of the planet and testing technologies for other planets like Mars. Looking into the future, we have a lot to learn from extreme landscapes and the way we have used resources there. In this context, experimenting with salt as a building material was a way of exploring this new relationship between materials, landscapes and architecture from a local territory.

Q: You tell stories through the spaces you design; how does this feature in your project?

A: I work a lot with communicating ideas and narratives through spatial design for exhibition design, commercial projects and art installations. Creating immersive and memorable experiences allow natural and synthetic ways for people to engage without necessarily knowing the whole context of a project. I explored this in my RCA project through multi-media experiences and alternative storytelling for museum contexts.In Salt Imaginaries, instead of making an information-oriented exhibition about salt, I created an immersive atmosphere inviting the audience to contemplate this salt wall while entering an alternate space of light, colour, and sound. I always try to think of spaces in a sculptural way, using scenographic components that can carry specific meanings and help to contextualise through minimal spatial interventions. The sun, for example, is a scenographic element that is slowly glowing and naturally brings to the space ideas about light cycles and the warm landscape of the desert, where the sun is the only reference of movement and orientation.

I also created a sculptural round piece where mineral rocks are displayed in a scenographic, almost ritualistic way, creating a central space for people to gather and sit down. The soundscape, by my collaborator Tom Burke, recreated the soundscape of the Atacama salt flats, where rocks are continually cracking everywhere like a natural mineral orchestra. A side colourful vitrine and a film walked people through key elements from the research and material experimental process, telling more detailed stories, from the desert to the making laboratory where I fabricated the tiles. In this way, while experiencing the atmosphere and salt wall, the audience can also understand where it comes from, how it was produced and why is it relevant.

Q: Your journey began in the Atacama Desert in Chile, what was it like to be there in this extreme landscape?

A: I have been in the desert a couple of times and was dreaming about working with it in more depth. This research trip was key to activate my research, as it was a way to re-discover this landscape through salt, exploring salt ranges and salt flats through their geological and extraction histories. It was a challenging and intense trip. Moving almost 500km with cameras and heavy equipment alone as a woman in the North of Chile is not an easy task. However, I was accompanied in different spots by local geologists, guides and local people who guided me through this landscape. Each of them shared their knowledge and personal opinions with me and together we documented the landscape, took samples and talked from sunrise to sunset about the beauty of minerals, the history of the Andes, indigenous cosmologies and current corporate corruption. Being in the open landscape of ‘la pampa’ is quite a unique experience. You can listen to nothing but the wind and the salt cracking everywhere in the ground. It is something that definitely inspired the way I developed my project and the kind of experience I wanted to create in the final outcome.

Q: How would you like people to respond or what would you like them to remember when they see your installation?

A: The overall spatial proposition as an exhibition space is to create a contemplative atmosphere where people can slow down and experience a different narrative space within the museum. There are many overlaying narratives in my research and catalogue, where I touch issues about mineral mining, disregarded materials, environmental problems, manufacturing processes, and future material alternatives. I expect people to engage in different and personal ways rather than proposing a directed interpretation of the work.

However, I ultimately would like visitors to feel intrigued or surprised by seeing salt as a building material that can create a beautiful and powerful aesthetic experience. I want to raise questions about disregarded materials and the gorgeous and complex landscape of the Atacama desert in Chile. I would like to know that after being in this space, visitors think about the way we value materials and what role can art and design play on this. Lastly, the atmospherical and experiential emphasis is a proposal to think about exhibition design in itself, and how important it is to bring narrative and storytelling into these spaces, which is something I carry with me from my MA at the RCA.

Q: If you could design anything else from salt, what would it be? Is there another disregarded material you’d like to explore with next?

A: Through this project, I opened a full range of possibilities with mineral materials from the Atacama Desert that I intend to keep developing through different projects and collaborations. I am now starting to work with other kinds of mining waste, which is a massive problem in Chile. There are more than 700 tailings of waste produced during the extraction process; a mix of various minerals and toxic components. I am also looking into mineral pigments which can be found everywhere in the desert in different types of minerals and soils. I love working with colour on the surfaces I design, and the beauty of this is that you can make pigments out of something as simple as the most disregarded materials of all: soil.

Q: What has been your best experience from the Design Museum residency so far? Do you have any advice for anyone thinking of taking part in the programme next year?

A: There were many highlights during the period of this residency. Having the opportunity to work collaboratively with the other designers and curators was fantastic, as it really helped to question and challenge my own ideas and ways of engaging with the audience of the Museum. We worked on a couple of collaborative projects for the London Design Festival and a collaboration with Arper, which were great opportunities to expand our work as a team. But most of all, having the chance to see people interacting with my work once the exhibition opened was by far the most exciting experience of all. Exposing your work to such a large and varied audience in London is incredible and is something I never experienced before.

Q: It’s International Women’s Day (8 March); do you have a message for young women considering a career in design?

A: As a woman, I struggled during the first years of my career. It was difficult to find my voice and make a space on my own, especially coming from a country with strong gender inequality in professional and cultural dimensions and poor education in these matters at the time.

After years of experience, I think it is crucial to feel confident about our creative power as female designers, and understand that our individual stories, personalities, memories, and relationships are also what makes us uniquely talented. This is something I always try to bring into my work, developing my ideas from a personal standpoint rather than hiding who I am or where I come from. Sadly, we are still living in a society shaped by discriminatory stereotypes and social blame on women, in which we can easily tend to feel guilty for things we shouldn’t and therefore insecure about ourselves, our capacities, and creative freedom. To succeed in art and design, we need to free up from that cultural insecurity. Design is about presenting new relationships with objects, materials, spaces, and people, and for that, we have to feel empowered to propose our vision of things from our experience of the world as women. We can bring new generations of design based on values that will help to build a more empathetic and sustainable future, so we must be out there shaping the ways we want to live through our own models of perception.

Related exhibition