Beazley Designs of the Year

Q&A with Fernando Laposse

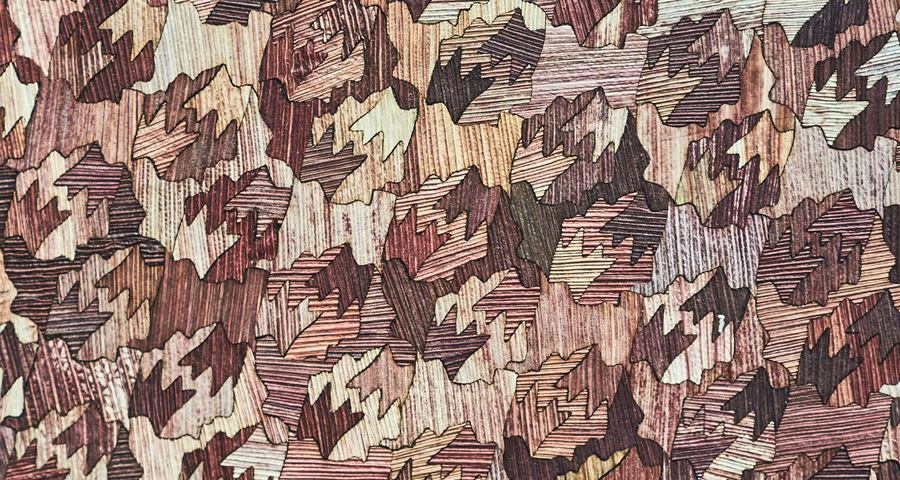

To mark this year’s Beazley Designs of the Year, the Design Museum speaks to Mexican industrial designer, Fernando Laposse about his striking pieces of marquetry made from the colourful leaves of native Mexican corn.His project, called Totomoxtle, poses questions globalisation, the food industry, employment and culture.

Q: Congratulations on being nominated for this year’s Beazley Designs of the Year, what does it mean to you to be put up for this award?

Thank you! For me it is a great validation of the efforts that me and my farmer partners have been doing for the past three years so I am very proud that Totomoxtle has been nominated for such a prestigious award.

Q: You have made beautiful pieces using a very unusual material, what first drew you to corn husks, and what made you see their design potential?

In my home country, Mexico, maize is the most important ingredient in every meal and without the domestication of corn we wouldn't have had the great pre-hispanic civilisations of mesoamerica. Therefore our cultural heritage is completely interlinked to the history of corn. Mexico has over 60 different kinds of corn and the native species grow in a diversity of wonderful colours. Unfortunately all of these species are in sharp decline because of industrialised corn. I saw using the colours that grow naturally in the corns of my country as inspiration because of the rich palette of textures and colours but also as a visual reminder of the diversity that we are losing at an alarmingly fast rate.

Q: You have called your new material Totomoxtle, where does this name come from?

The hope of preserving native corn really lies in the indigenous communities of the country which continue to plant it because it is essential to keep their traditions alive rather than planting it for financial gains. I decided to call the project Totomoxtle because that’s what the corn husks are called in Zapotec and Nahuatl, two of the most spoken native languages. If you want to get corn husks in the south of Mexico, you must ask for Totomoxtle!

Q: The production of Totomoxle uses a completely sustainable system, can you describe the process, and do you think the environmental impact of manufacturing is becoming a more important factor for designers?

We are reintroducing some of the critically endangered species of coloured corn with the support of a seed bank that has provided seeds from their vaults. After 7 months from the day we plant, we can harvest the corn. The husks are then ironed flat by hand and cut using a press die cut or a laser cutter everything is then hand assembled and bonded using a heat reversible glue. All the trimmings that don’t get used to make the material are composted in an earth work digester which is owned by the community to make new soil compost to fertilise the fields in preparation for the next harvest. Every season is different, the sizes might vary, so I have to adapt my designs to the results of every harvest.

I think the impact of manufacturing is definitely a more important factor for new designers. Which is a good thing. The problem is overseeing the whole process, that’s a lot harder!

Q: There is a long tradition of corn farming in Mexico. Did you experience any resistance when you approached the farmers about this new way of working and what has been the impact to their lives?

At the beginning I did, but not because I was suggesting a new idea because actually what I was proposing was to go back to their traditional techniques. I faced scepticism in the community because many were afraid of having their land taken away from them. Land right issues are still a very serious problem in Mexico and indigenous communities are often dispossessed and displaced from their land. The project would have been impossible without the help of Delfino Martinez, a community leader who I have known since I was six years old and who vouched for my idea and helped me approach other members of the community. Without our lifelong friendship I would have never been able to convince the rest of the farmers to join my project.

Q: What role do you think design has to play in ensuring the future of biodiversity in the food production industry?

This might be oversimplifying the question since I see design pulling this issue in all sorts of directions. There seems to be a lot of efforts in design towards a package-less future, food that gets 3D printed,"bio products” made with food derivatives etc. But I think there are very few cases in which designers are relocating to the source of food, living with farmers for a considerable time. I am not sure design has the power to create a one size fits all solution for the loss of biodiversity because its root problem is not one of production methods but rather one of legislation.

I think the way design can help preserve biodiversity is by using its power as a communication tool to give a voice to farmers that are being forced to abandon their traditional ways of life because of economical and political pressures.

My project will never make a dent in the global corn trade but it is a first step in taking a stand against how things are being done.

Q: Are there any other plants or produce that you would like to work with?

I have recently started working with sisal, the fibres of the agave cactus also native to Mexico. In the past sisal was the main material for making ropes and fishing nets, it used to be a massive industry which supplied thousands of jobs to indigenous Mayans in the south of the country. Sadly, the production of sisal came to a grinding halt with the advent of nylon and other plastic fibres. In my opinion tackling issues like plastic waste in the future is not so much about making new magic materials but also looking back to the ones that were already working well in the past.

Q: What’s the one thing you’d like people to remember about your designs when they leave the Beazley Designs of the Year exhibition?

I hope visitors leave with a good idea of the whole story behind the project and that this will make them carefully consider the ramifications and real cost of the over abundance of ingredients we now have access to. Hopefully this will allow them to make more informed choices when buying food and hey, why not, also when voting!

Q: And finally, if you had one piece of advice for a young designer starting out, what would it be?

I would recommend finding a topic that you are very passionate about. Something that will keep you motivated to pursue despite adversity over the years. In my opinion, all good projects take a very long time to bare fruits and it is the people that persevere that get to reap the benefits. Design trends come and go so it is important to produce projects with substance that will stand the test of time.

Related exhibition