Beazley Designs of the Year Blog article

A time-honoured teapot | The Brown Betty

Ceramicist Ian McIntyre set out to understand how the Brown Betty became ubiquitous in Britain. He worked alongside Cauldon Ceramics, the oldest surviving manufacturer, to re-engineer the design and make it profitable once more.

In this special blog feature, Ian talks about the teapot's design evolution and the historical and social practices of tea-drinking in Britain.

Ian dressed as a Brown Betty teapot

Hello, I’m a designer and ceramicist based in London and currently studying a collaborative Doctoral Award with Manchester School of Art, York Art Gallery and The British Ceramics Biennial. I’m also the designer of the Re-engineered Brown Betty Teapot, which is currently nominated for Designs Of The Year 2018. The re-engineering of this teapot has involved three years of research into the history of the object. Like many PhD students, I have developed a mild/extreme obsession with my subject. The Design Museum team have asked me to share this obsession with you through a brief history of this iconic object.

An original Brown Betty | Photographed at Vitsœ, image by Geoff Howe

An everyday archetype

The name Brown Betty describes a type of teapot with common characteristics of red Etruria Marl clay, a transparent or dark brown Rockingham Glaze and a familiar portly body. The popularity of the pot is proven in the quantity in which it has been made – it was estimated that by 1926 the Staffordshire pottery industry were making approximately half a million per week! This teapot was a best seller for the design retailer Habitat in their early years, it is a favorite of Sir Terrence Conran and also features in Phaidon Design Classics (2006). Despite this, surprisingly little is known about the object itself or its’ early history and design development. This affordable, utilitarian and unpretentious object has largely gone unnoticed, disappearing into the fabric of everyday life.

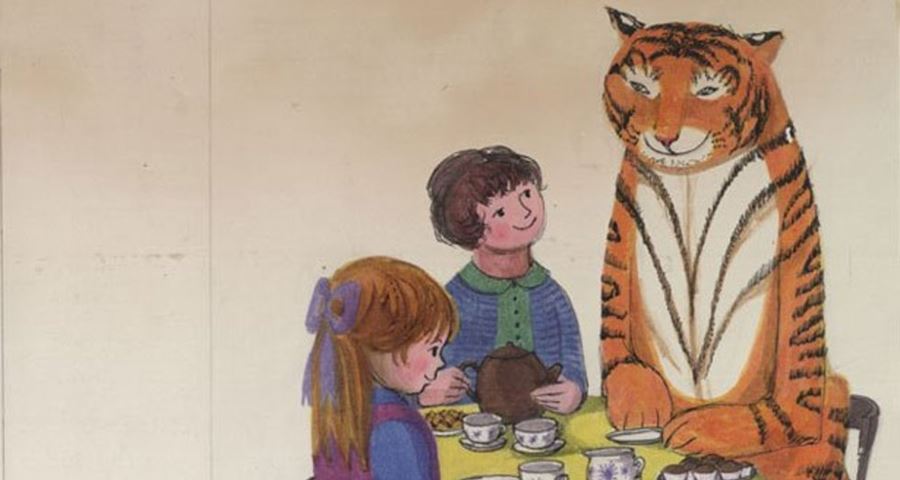

Brown Betty in The Tiger Who Came For Tea, Judith Kerr

Origins

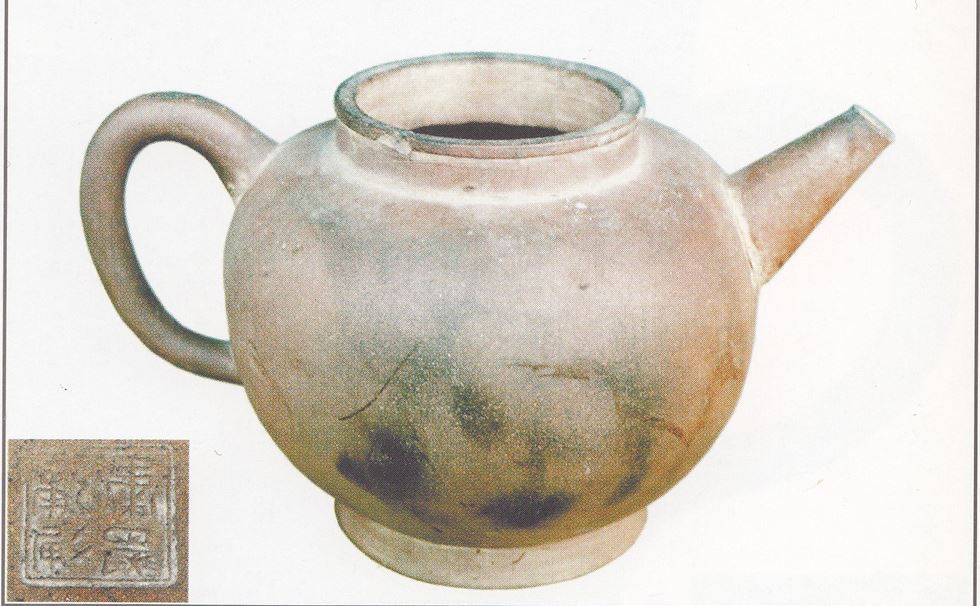

The process of design of the Brown Betty spans centuries and although seen as quintessentially British, the pots origins are global: first influenced by Yixing teapots originally made in China during the Ming Dynasty and which began to arrive in Europe via Dutch East India ships, along with tea, from the 17th century. In the early 1600’s tea was prohibitively expensive and the market was contained amongst extremely wealthy society such as royal courts and aristocrats. The trade remained small, but from 1660 - 1700’s the leaf and the Yixing pots began to assume a wider role in high society life in both Holland and England.

As Europeans developed a fascination for the pots, Dutch potters began to emulate them. In a letter sent to the States of Holland and West Friesland 1679, two potters from Delft - Sammuel Von Eenhoom and Ary DeMilde requested sole privilege to produce imitations: “we, associates, have discovered production techniques which make it possible to copy the teapots from the East Indies. We request permission to produce these pots for 15 years and to be the only ones to market them”. Not long after this, potters in England began to reproduce them too.

Early Ming Dynasty Yixing teapot

Dutch Elers brothers teapot, immitation of Yixing from V&A archive

Characteristic Clay

The combination of the Rockingham glaze and the red clay was and still is fundamental to the success of the Brown Betty, prolonging the life of the object for its owner and, subsequently, through history. The Staffordshire clay used to make a Brown Betty was first refined in the late 1600’s. Two Dutch brothers - John Philip Elers and David Elers played a key role in this process. They began to reproduce the fashionable and expensive Yixing teapots from a small workshop in Bradwell Woods, North Staffordshire, England. The refinement of this local clay to make redwares gave rise to a new era of technological experiment in the area, and is now seen as a key catalyst for the industrialisation of the six towns that now make up Stoke-on-Trent.

Image by Bjarte Bjørkum

Anonymous and evolved

Though still an expensive commodity, by the early 1700’s, tea had been introduced across all levels of society. The leaf had become available to purchase from ‘Coffee houses’, ‘India houses’, and apothecaries, and servants in England began to receive the drink as part of their wages. By the 1720’s competition between European trading companies drove the price of tea down and in 1745 the excise tax on the leaf was reduced. By the 1750’s the desire for table wares and hot drink utensils had created such an extensive market that these objects became common in English homes. By 1750 the early development of salt and lead glazing had taken place in Staffordshire and redware teapots began to appear with glazed surfaces. It is likely that the Brown Betty first became a familiar object around this period along with the mass acceptance of tea as a drink and the start of British industrial pottery production.

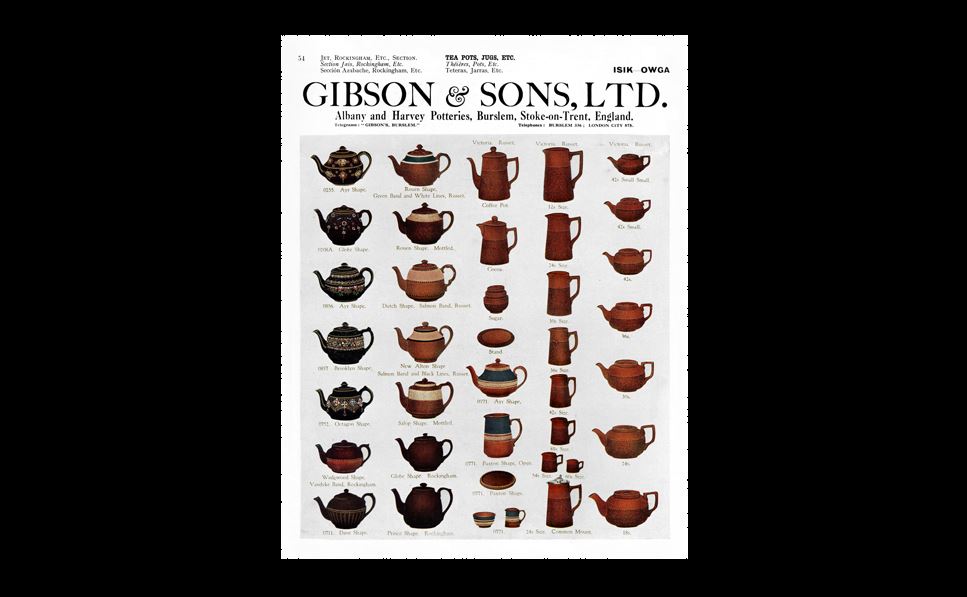

By the mid 1800’s there were numerous factories producing the Brown Betty in various shapes, sizes and styles and a shift had taken place. These pots had become cheaper (reflecting industrial prices and the lower cost of tea). Amongst the more notable firms making these were household names such as Gibson&Sons and Sadler, a slogan in one of their adverts reads ‘Cheap – but good’. There is no single identifiable designer or maker and no single definitive version: these objects are anonymous and evolved.

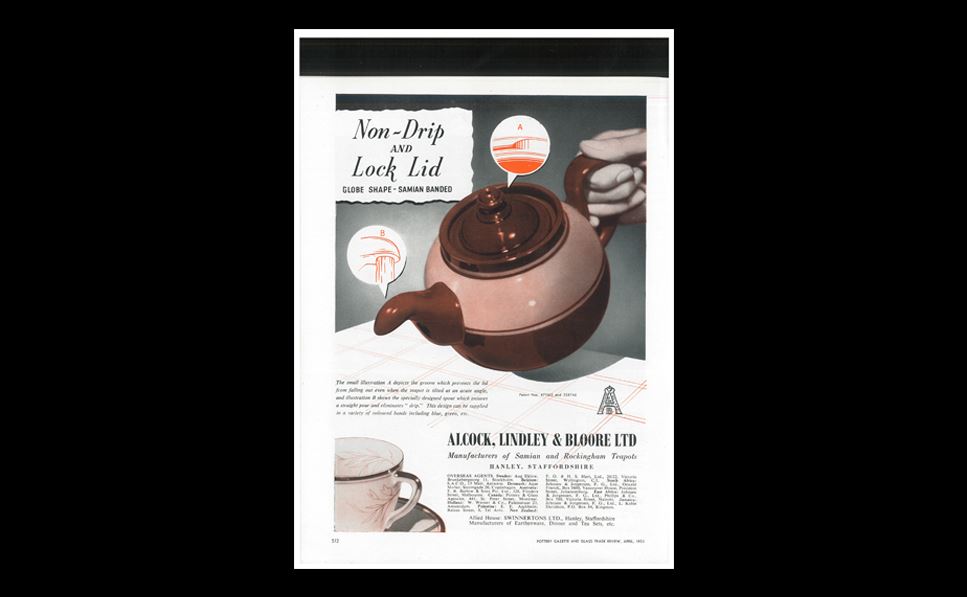

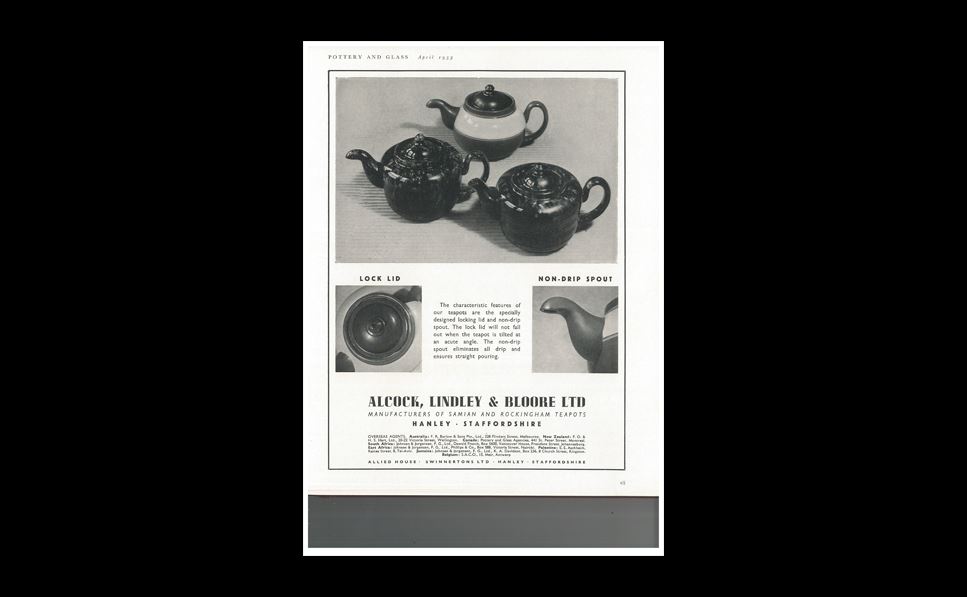

Over the years, Brown Betty has been through the hands of numerous makers; each producing their own interpretation, and subtly refining and amalgamating new and original design details. The resulting teapot is often a rational design stripped of anything superfluous to its function or production - the globe shape of the pot that is so efficient at infusing loose leaf tea, the roughly cut spout that breaks the flow of water, preventing tea from dribbling back down the outside of the pot and the Rockingham glaze that concealed any dribbles that did, despite best efforts, escape.

Alcock Lindley & Bloore, advertisement

Gibson and Sons advertisement in The British Pottery Manufacturers Federation Standard Exporter (1929), image courtesy of Manchester Metropolitan University Special Collections

Original Alcock Lindley & Bloore advertisement

A sympathetic Re-engineering

Cauldon Ceramics of Staffordshire maintain the tradition of redware manufacturing and are the oldest remaining maker of the Brown Betty teapot in the UK. Production is a scaled down operation compared to the early 1900’s - in relatively recent years a combination of low perceived value, outsourcing and cheap inauthentic imports have decimated the industry. Over the last two years, I’ve worked closely with this maker to develop the re-engineered edition which is designed to re-appraise the objects history and value. The new edition includes reintroduction of innovative precedents in the history of the pot: A patented ‘locking lid’ and ‘non-drip spout’ from the 1920’s have been applied. Plus there are new additions such as a subtle tweak to the foot and neck of the pot allowing the lid to be inverted into the body, enabling it to be stored efficiently in the factory and stacked in cafes and restaurants. A loose-leaf tea basket has also been added.

Great care has been taken to respect the traditions of the Brown Betty whilst implementing new production processes and design details. I felt that to re-style the pot, would have been a disservice to the years of refinement that have gone before. This latest edition is intended to promote the legacy and value of this everyday object, that has transcended fashions and trends to become a reliable and dependable tool for millions around the world.

Instagram @_ianmcintyre_

Twitter @_IanMcIntyre_

Website www.ianmcintyre.co.uk

Back stamp, image by Ian McIntyre

Ian McIntyre, Brown Betty development, image by Angela Moore LR

Cauldon factory, image by Gareth Gardner

Cauldon factory, image by Gareth Gardner

Ian McIntyre, Brown Betty packaging box, image by Angela Moore LR

Ian McIntyre, Brown Betty spout, image by Angela Moore LR

Related exhibition

Background image | Brown Betty Group, image by Angela Moore LR