Hope to Nope: Graphics and Politics 2008 - 2018

Q&A with Milton Glaser

To mark the Hope to Nope: Graphics and Politics 2008-2018 exhibition, design educator, writer and co-founder of GraphicDesign&., Rebecca Wright, American graphic designer, Milton Glaser.

Glaser's designs include the I ❤ NY logo, the psychedelic Bob Dylan poster and the Brooklyn Brewery logo. In 1954, he also co-founded Push Pin Studios and received many awards for his work, including the National Medal of the Arts award from President Barack Obama in 2009, and was the first graphic designer to receive this award

Milton Glaser, co-founder of Push Pin Studios, is one of the world’s most admired graphic designers, a gifted artist and a distinguished illustrator. He has had a long, politically active career working on identities, campaigns and as a faculty member at New York’s School of Visual Arts (SVA). One of his most famous works is the 1977 ‘I ❤ NY’ logo, created pro bono when the city had a reputation for violent crime. More than 40 years later, the image is still inextricably linked with the city, and is familiar to millions of residents and tourists, as well as having been copied, quoted and parodied everywhere. Glaser made beautiful posters for Olivetti, as well as a range of memorable album covers, magazines and corporate identities. With designer Mirko Ilic, Glaser wrote and compiled The Design of Dissent (2005). Its follow-up, The Design of Dissent: Greed, Nationalism, Alternative Facts, and the Resistance, was published in 2017. Glaser’s most recent design work includes provocative poster campaigns urging action on climate change (‘It’s Not Warming, It’s Dying’) and encouraging people to vote in the US presidential election (‘To Vote is to Exist’).

Q:

You’ve talked about art and graphic design as vehicles for change. What impact do visual artists have on the way people understand messages and act on them?

Art, to my mind, has always been a mechanism for developing the best capacity of the human spirit. In the presence of great art, you are transformed and more generous to others. I distinguish between this and art that’s produced to persuade, to make people do things they don’t necessarily want to do or buy things they don’t necessarily want to buy. The question is: who benefits? If you see a poster and realise that all it’s doing is encouraging your child to drink more soda, you’re not in the hands of someone who cares about your life, but someone who wants to profit from your activity. Graphic design doesn’t have an abstract purpose. It has specific purposes, one of which is to inform and transform. Another is to sell stuff to people and encourage consumerism. These are two different activities and it would be useful if graphic designers and others distinguished between them. They are usually lumped together. People aren’t aware of these differences – the real purpose of what graphic designers do is usually ignored, whereas it has significance for us all.

Q:

Technology makes it easier for everyone to create visual political messages. You have designed many political posters and have said the greatest technology is still the human brain. Is this the most important factor in how political messages are viewed?

The most important thing about a poster is its capacity to move the mind. That often depends on the astuteness of the imagery. Designers and makers use visual poetry to form connections in the mind that are not easily made visible. It’s a way of saying, ‘Look, these two things have a relationship.’

The way you think about your kids’ education has something to do with the nature of the economy, for example. To make these connections, we draw upon the largely unconscious observations we make when we want to express something to others.

Political posters are often ineffective because their tone is violent. When somebody attacks you, your impulses are not to surrender but to fight back. My concern about most political material is that it is not thoughtful. These are often pieces that satisfy their maker and express their rage, but they do not change other people’s opinions. In political action, you want to transform people’s vision – you want them to agree with you and act with you. The issue about urging people to vote is that it’s not enough to say ‘Go vote’, for example. You have to tell people why. For me, if you don’t vote, you’re essentially invisible, which is what my poster, I hope, conveys.

Milton Glazer it's not warming courtesy of the School of Visual Arts

Q:

Can you tell me how your SVA Subway Series posters came about? They’re obviously compelling visually, and demand an emotional response, but why did you design them and why now?

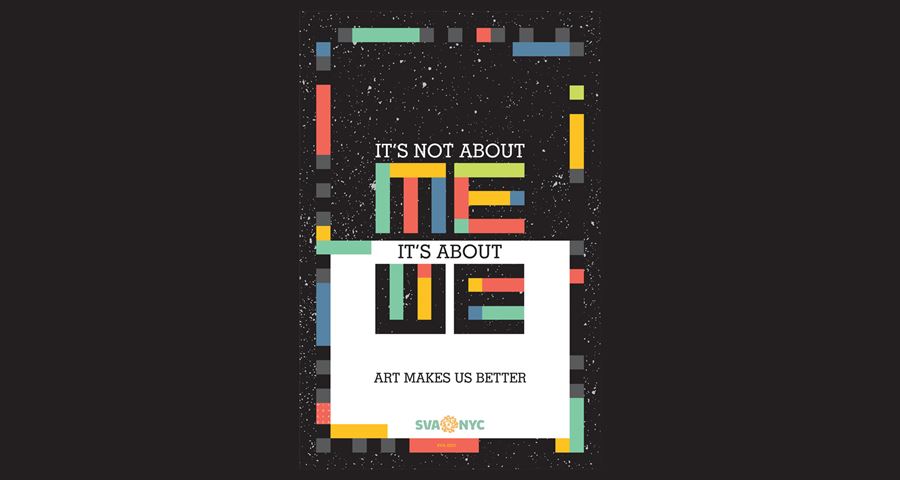

Since the 1950s, the SVA has featured the work of practising faculty members as part of poster campaigns in New York’s subway stations. My recent SVA posters are all political. All three attack assumptions made by the Trumpian universe. ‘It’s Not About Me, It’s About We’ is an attack on Trumpian narcissism – you can take whatever credit you want, but you are not the universe and all of us are in this together. The purpose of the world is not to enrich some and ignore others; it is to transform the human spirit so we all recognise our common objectives.

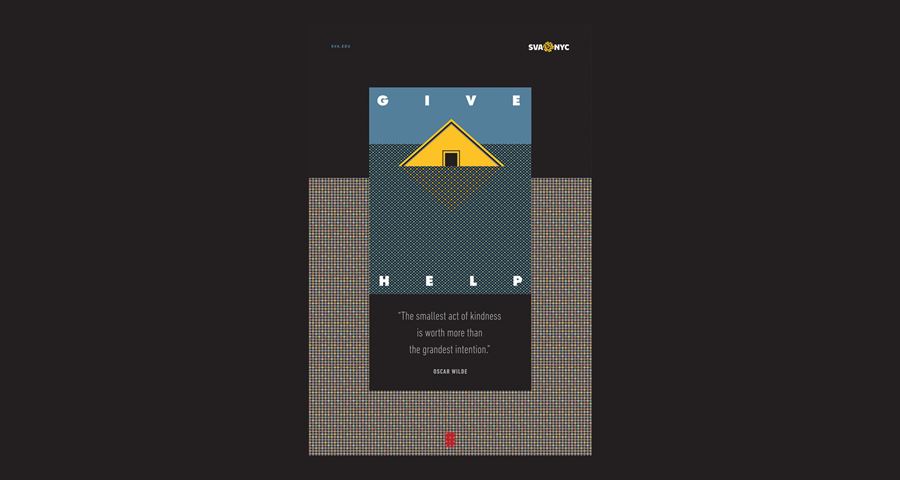

‘Give Help’ is an attack on Trump’s view of the ‘other’. It shows a submerged building and is a reference to the US territory Puerto Rico, and how slow and indifferent the US government had been in aiding its recovery since 2017’s Hurricane Maria.

Essentially, Puerto Ricans are not considered Americans because they are darker skinned. It is a reminder of the fake promise that Trump made to take care of them, which hasn’t happened. It is also a reminder that Trump has made false promises to us all.

‘To Dream is Human’ is a universal message that also has a specific political meaning in the US. ‘Dreamers’ is a term derived from the DREAM (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act and refers to some 700,000 undocumented immigrants who arrived here as children, mostly from Central America. Obama granted them rights that Trump wants to roll back. The poster is about shifting the idea of a dreamer as somebody you don’t want in your neighbourhood because they are somehow beneath you to the idea that to dream is the most important thing humans can do. It’s a shift of language – this is the germ I want to plant in people’s minds.

Q:

Your ‘I ❤ NY ’ logo has resonated for years, becoming even more significant post-9/11. Climate change is such an important issue now. Can you tell me more about your ‘It’s Not Warming, It’s Dying’ campaign?

As a designer, it’s very hard really to know the results of what you do. You never know what changes people’s perception. When I did the ‘I ❤ NY’ campaign, I thought it was going to be around for two weeks and then disappear, but it turned out to be extremely persuasive and durable. It actually had an effect on life in the city. Because it rang true, it was powerful in making people act in a different way. So I have had a few experiences – not many – where I did something that changed an existing condition. This, of course, is the greatest reward in graphic design; when you do something that changes the human condition for the better. The question for us all in the profession, which is too rarely asked, is, what are the consequences of my work?

‘It’s Not Warming, It’s Dying’ is an example of something that hasn’t yet entered the system. Even though SVA had it on the side of a building, and gave out badges, it never quite entered into public consciousness. One reason may be that there are a lot of other expressions of this idea. Another is that the world’s ruling political and financial powers don’t want to act to end global warming – this group’s interests are the most powerful forces in our culture. Campaigns like this seem to be going nowhere, but you never know where the tipping point is, of course.

Q:

Recent political events have felt catastrophic. Do you feel any sense of hope?

You know, late in life, I question much more – even the simplest decisions that I used to take for granted. I take a longer view, too, perhaps a more Buddhist approach about what is good and what is bad and what we should be in favour of, and so on. With distance comes humility, and the idea that perception – the mind – creates everything. With this comes a sense of optimism.

Milton Glaser in situ photos courtesy of the School of Visual Arts

Find out more