Head of Invention

Discover the influence of Scottish sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi on Terence Conran and find out more about the iconic Head of Invention sculpture now displayed at the entrance of the Design Museum.

The sculpture was created by Eduardo Paolozzi, one of the most important artists to emerge out of Britain during the post-war era. It was commissioned by the Design Museum’s founder, Sir Terence Conran, to commemorate the opening of the museum in 1989.

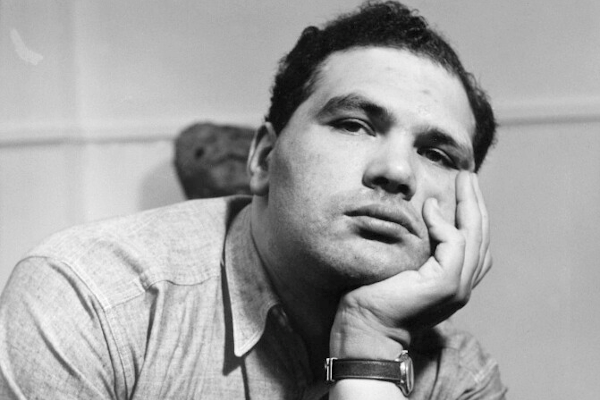

Eduardo Paolozzi, photographed by Ida Kar in November 1958, National Portrait Gallery.

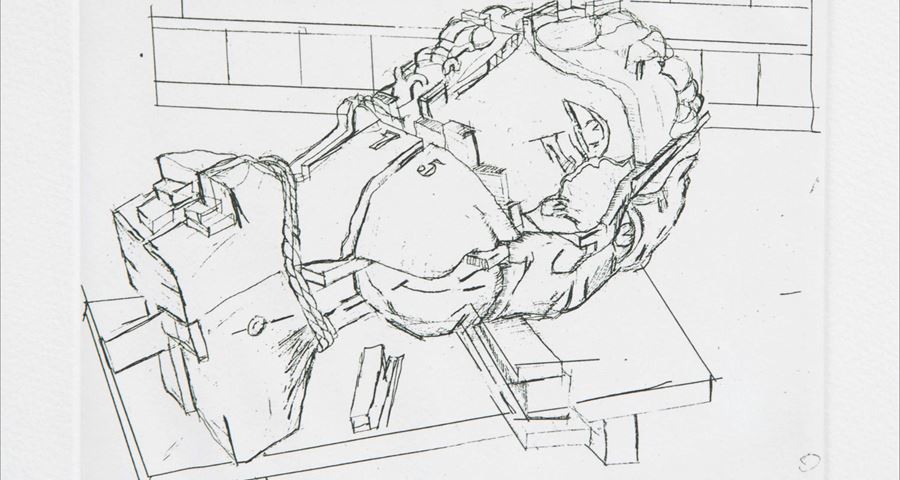

Etching of the Head of Invention, 1989. The stark, geometric building behind is clearly a stylised representation of the Design Museum’s Shad Thames home.

But this was more than just a straightforward commission, nor was it a bland commercial transaction. Rather, the commissioning of the Head of Invention was one part of a lifelong collaboration and friendship between Paolozzi and Conran. Their careers had different paths, but it’s nonetheless fascinating to trace the ways in which their lives overlapped and to see how they worked together.

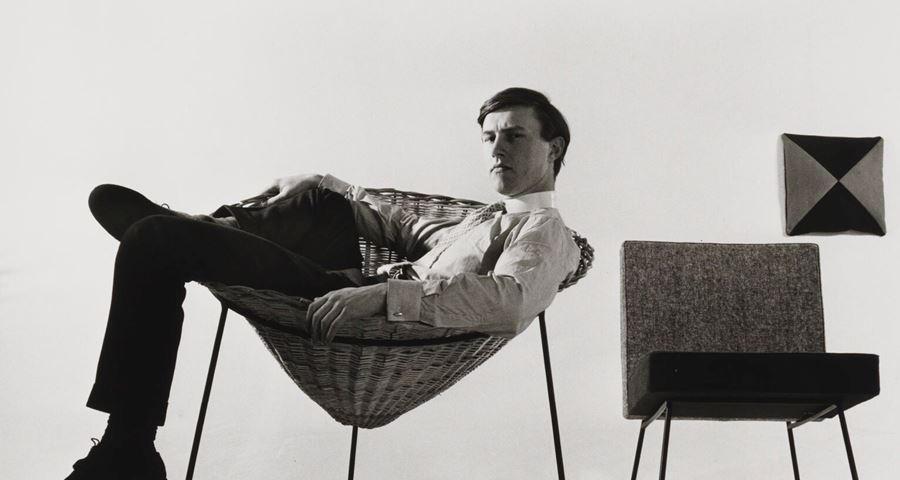

A young Terence Conran, photographed by Ray Williams in the 1950s, National Portrait Gallery.

Between 1949 and 1955, Paolozzi taught Textile Design at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. One of his second-year students happened to be Conran, who confessed to being immediately impressed by Paolozzi. During these early years, Conran recalled Paolozzi assembling collages “with enviable ease and confidence. He’d dip a pen into black ink and every mark he made was just right – even the blots seemed totally under his control”.

A selection of furniture and fabrics designed by Conran in the early 1950s, on display at the Design Museum in 2011.

The two quickly struck up a friendship. Paolozzi taught Conran about textiles, patterns and art, and the two men shared a workshop in Bethnal Green, London, where they acquired simple tools and basic welding equipment and set about making things. Materials and equipment were scarce in the post-war years, so they would scrounge bits of old metal from building sites and textiles from stalls on Petticoat Lane.

An architectural model of the Festival of Britain on the South Bank, c.1950.

One of their most notable collaborations was in 1950, when they assisted architect Jane Drew in her design for the new Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA), which was then located in Dover Street. Under Drew’s direction, Paolozzi and Conran helped create the interiors and furniture for the forward-looking organisation. Although Britain was still very much recovering from the war, this was nonetheless an exciting time to be a designer – the 1951 Festival of Britain provided numerous opportunities for work. Paolozzi was commissioned to build a fountain for the Festival, while Conran dropped out of college to take up a job with architect Dennis Lennon where he designed several structures for the Festival.

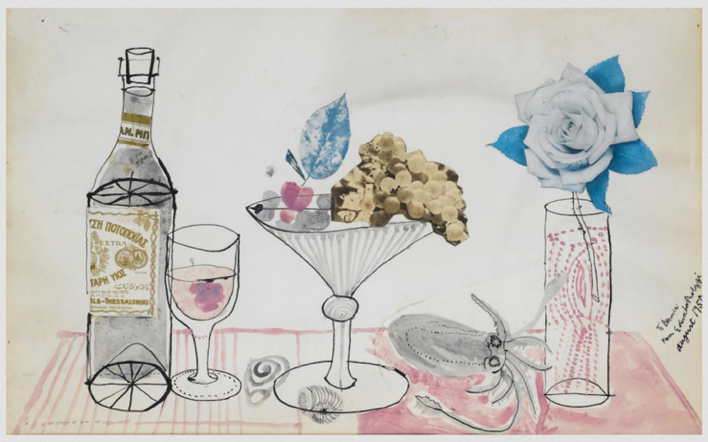

Eduardo Paolozzi, Still Life with Rose, 1950. It is signed ‘To Brenda / From Eduardo Paolozzi / August 1950’.

During this time, the two men lived near each other in West Kensington, just off Kensington High Street (close to where the Design Museum is today). This collage is inscribed to Brenda Davison, who had renovated the house where Conran was living in Warwick Gardens (and who later married Conran). Paolozzi was a frequent visitor, because, according to Davison, “where he lived was so horrid”.

It would not be a stretch to say that Paolozzi was a life-changing influence on Conran. He introduced Conran to food. “We were all poor students and constantly hungry,” recalls Conran. “There was still rationing in Britain and we pretty much survived on Spam sandwiches, which is no way to live. But Eduardo used to invite me to his flat because he got these wonderful parcels of food sent over from Italy. One night he cooked me a squid risotto with black ink and it was like nothing I’d ever tasted.” As Conran puts it, Paolozzi taught him how to cut an onion. In return, Conran taught him how to weld.

Members of the Independent Group pose in a photograph for the ‘This is Tomorrow’ exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, 1956. From left to right, Nigel Henderson, Eduardo Paolozzi, Alison and Peter Smithson.

As the 1950s progressed, their paths began to diverge. Paolozzi’s career quickly took off and much of his work had an influence on the eventual direction of Pop Art. He was also a leading member of the Independent Group, a cross-disciplinary group of artists, designers and theorists that met at the ICA between 1952–5, including personalities such as artist Richard Hamilton, theorist Reyner Banham and architects Alison and Peter Smithson.

Likewise, during the 1950s, Conran established a number of design businesses and restaurants with dizzying speed. His crowning achievement was Habitat, the highly influential retail chain he founded in 1964. Through Habitat, Conran had a near-undeniable impact on the way we choose to live, and his influence lives on today. In the picture, the second edition of the Habitat catalogue, 1971.

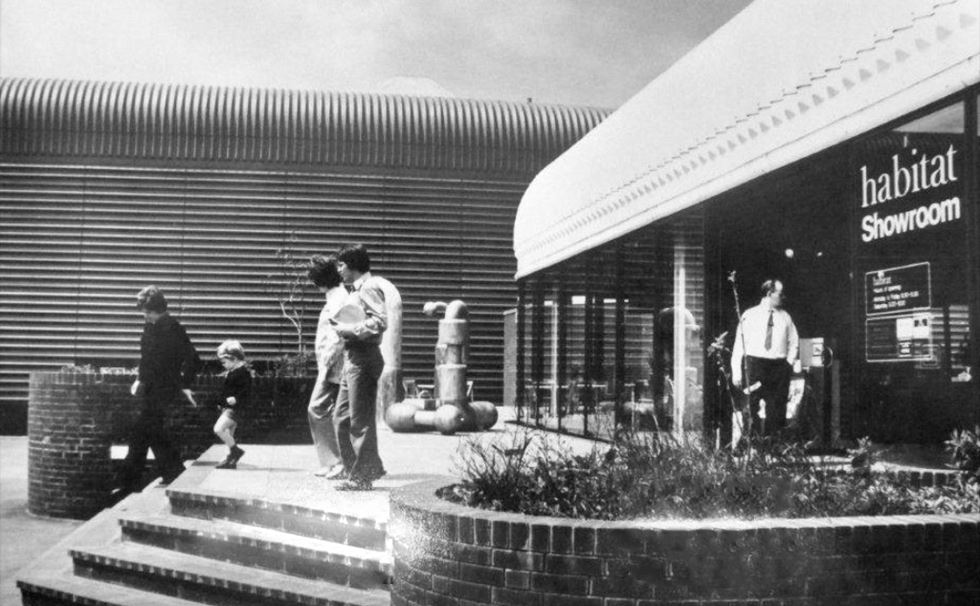

Paolozzi’s ‘Yantra’ (1973-74) at the entrance to the Habitat showroom in Wallingford, c.1970s.

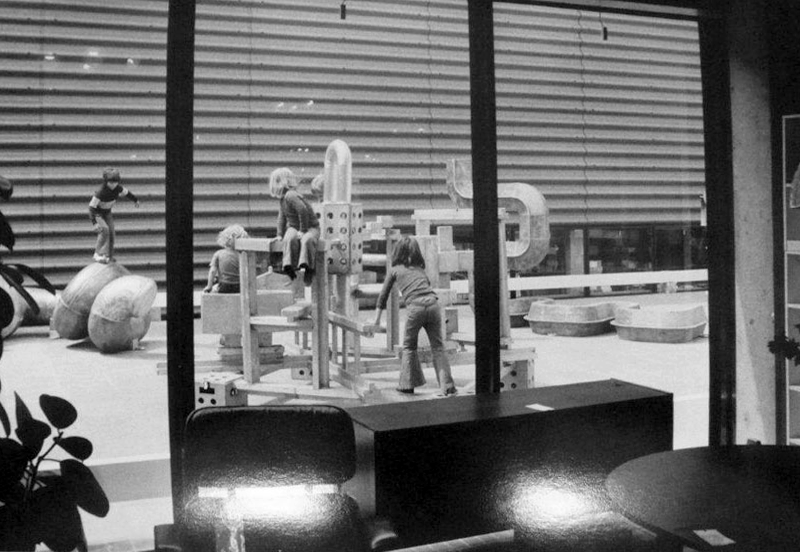

Eduardo Paolozzi’s ‘Suwasa’ (1966) in use as a playground at the Habitat Wallingford showroom. The sculpture was originally commissioned for the Economist Plaza in London, designed by Alison and Peter Smithson in 1964. Photograph by John Donat.

The playground as seen as from the windows of the Habitat showroom, c.1970s.

But Paolozzi and Conran’s collaborations did not end there. In 1971, Conran commissioned Paolozzi to build a children’s playground for a new Habitat warehouse and showroom in Wallingford, Oxfordshire (designed by architects Ahrends, Burton and Koralek). For this project, Paolozzi built three new sculptures and incorporated pieces from several earlier sculptures that were no longer on display.

Eduardo Paolozzi, ‘Manuk’ (1973-74). Image © Estate of Eduardo Paolozzi.

This is a sculpture that can be touched, climbed on and explored. For Conran, the commission was a way to introduce children to modern sculpture through play – and, from these photographs, it’s clear that children delighted in clambering over these welded aluminium pipes and beams that appear to twist and turn over each other.

The Head of Invention in front of the Design Museum in Shad Thames in 2004. Photograph by Martin Pettit.

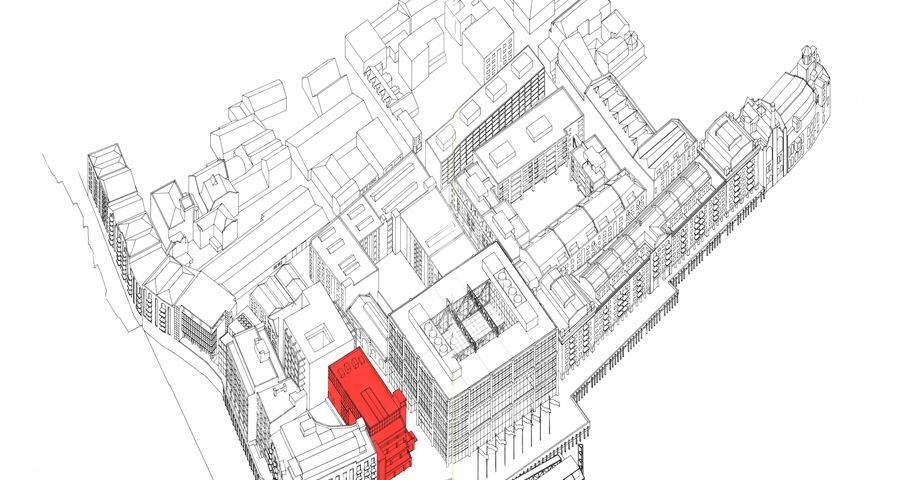

And finally, we come back to the Head of Invention, this time as another commission for the Design Museum’s Shad Thames home. The opening of the new museum was to be the flagship venture of Conran’s redevelopment of Butler’s Wharf, an 11-acre site of near-derelict Victorian warehouses and wharves.

Before its conversion, the Design Museum’s home at Shad Thames was a banana ripening warehouse and a Korean army surplus store.

The Design Museum at Shad Thames, shortly before its opening in 1989.

In 1956 Paolozzi played a docker in Lorenza Mazzetti’s experimental film, Together, much of which was filmed in the Butler’s Wharf area.

Part of Butler’s Wharf’s appeal was its riverside location, on the banks of the Thames and with a spectacular view of Tower Bridge. To make the most of the view, Conran planned a pedestrianised riverside promenade that would be lined with bars, shops and restaurants. Paolozzi’s commission was to occupy a prominent position on the promenade, alongside salvaged elements such as anchors, heavy chains and mooring posts.

An axonometric highlighting the Design Museum’s location within the Butler’s Wharf development.

In many ways, Paolozzi was the ideal choice for this new public sculpture. He was inspired by the mass media, science, technology and their relationship with the modern world – themes that would also concern the new Design Museum.

Eduardo Paolozzi, maquette for ‘Newton after James Watts’, 1989. Photograph by Jasper Fry.

The finished sculpture is a gargantuan human head lying on its side, split vertically and horizontally. The back of the head is incrusted with the impressions of machinery, nuts and bolts, and wedges embossed with Italian words are driven into the gaps – taken from a quotation by Leonardo da Vinci, reproduced on its side: “Though human genius in its various inventions with various instruments answer the same end, it will never find an invention more beautiful or more simple or direct than nature because in her inventions nothing is lacking and nothing superfluous.”

Details of the sculpture

Although the sculpture is popularly known as the Head of Invention (possibly because ‘Inventione’ is one of the more prominent embossed words), Paolozzi’s own title was ‘Newton after James Watt’. Watt was the Scottish inventor and engineer whose improvements in steam engine technology were the driving force behind the Industrial Revolution. There are several allusions to steam technology; a heavy, cast-iron wheel rests underneath the neck, and the sculpture is held up by several railway sleepers – both nods to the steam-driven locomotive, one of the most important developments of the industrial revolution.

The Head of Invention in front of the Design Museum in Kensington.

The Head of Invention is a powerful piece. Paolozzi blurs the line between the man and the machine – a theme that is common to much of his work. It can be difficult to know how to read or understand the sculpture. It appears to be both an evocation of amazing advances that humanity has made in the fields of technology and simultaneously a reminder of the destructive or traumatic potential of the industry. Either way, both interpretations are appropriate for the Design Museum’s mission to investigate the impact of design on the modern world.